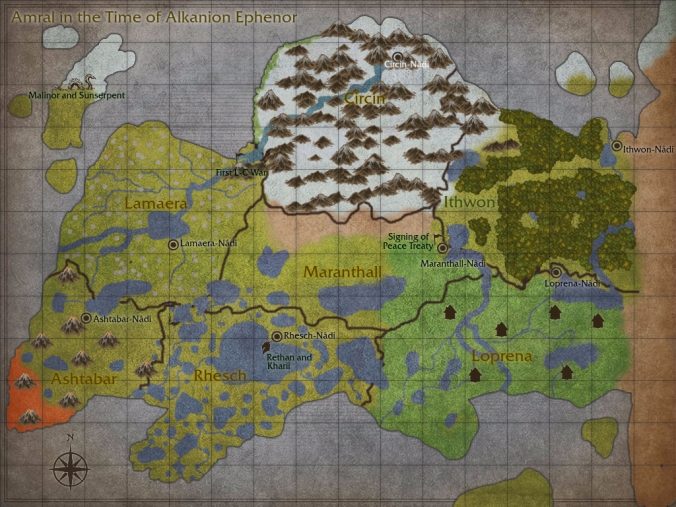

Amral was a magical land that could best be likened to our Europe, in the sense that it was a continent attached to a much larger landmass along its eastern border. However, unlike Europe, it was comprised of only seven nations, and, while the borders were sometimes disputed, the true identities of these nations could never be lost. This was because each section of Amral had its own unique magic infused into its very geography, and the people who lived there naturally became imbued with it over time.

The different kinds of magic, or haereldiar, were separate entities, at times almost incredibly so, but they were not all equal in power. Consequently, as the tribes of Ithwon developed into stagnant societies, a certain hierarchy developed right along with them, ranking the peoples according to the “purity” of the magic that flowed through their veins. However, while in some respects this was akin to a caste system, each person being delegated a place in life (or relegated to one), it was not nearly as socially binding as you might think. Intermarriage was common, and very few positions made a habit of denying onhaereldiar, or the “impure”–those that did often required the overt use of complex magic, such as the job of Lamaeran mage.

The final ranking for the nations was as follows:

- Lamaera

- Ithwon

- Ashtabar

- Rhesch

- Circin

- Loprena

- Maranthall

Each nation was unique in both culture and landscape.

Lamaera was widely considered the most sophisticated nation in terms of magic and engineering. They valued knowledge very highly, and consistently looked to the future, to new possibilities and ideas that would eventually leave them with an awe-inspiring legacy. Having had a long obsession with the sky, they adored the stars, the sun and moon, the clouds, the weather, the wind–anything relating to the air. One of their most famous inventions was that of the flying ship, enchanted to sit in a cradle of mist and water and to float through the air almost indefinitely. Their land was also home to the sylvanor trees, made of brilliant, easily-enchantable silver bark that was strong, yet supple; reaching, at times, almost a hundred feet tall; and having a dense, umbrella-like shade of leaves that could stretch a quarter-mile in either direction.

Ithwon was the primary home of historical knowledge, wisdom, traditional values, the arts, and many artisan crafts. The Ithwonians had a fascination with time, to the point where they erected a gigantic monument called the rose chroniker in their capital city, Ithwon-Nâdi, that used natural light to display the time for all to see. Its political system was the most measured, reasonable, benevolent, and kind, and, having been blessed with rich resources– from lush, thick evergreen forests, to a northern coastline teeming with fish, to an absolute embarrassment of precious gems and metals just waiting to be mined–few citizens of Ithwon wanted for much. In fact, Ithwon-Nâdi was considered one of the most beautiful places in Amral, not least because it was made almost entirely of precious materials and glass.

Ashtabar was considered a war country. Situated by the western sea, it was a fiery land full of volcanoes, lending it a perceived air of danger and foreboding to outsiders, who imagined it a desolate, magma-filled wasteland where inhabitants found joy in fighting to the death. However, in reality, Ashtabar’s volcanic activity granted it particularly lush soil, and, unlike the first two nations, whose magic was so pure that it could only be channelled with training, the Ashtabarans could all manipulate the ground well enough to glean two harvests every year: one early summer, heated by the underground magma pools as much as the sun, and one in autumn, arriving at what most consider the “normal” time. That being said, despite their agricultural abilities, Ashtabar did have a famously hot temper, often setting them at odds with calm-yet-stubborn Ithwon and, to a lesser extent, with idealistic Lamaera. Their violent image was not entirely unwarranted.

Rhesch was the country of lakes, and its people, lacking the ability to truly tame such a wide, mostly unfarmable expanse, developed a much closer, symbiotic relationship with nature. While their fishing trade thrived and some tiny farms did spring up, Rheschans generally survived using resources beyond their control. In particular, the other nations stood in awe of the kharii, or lake-dragons, that inhabited each lake and fostered an amazingly close relationship with the Rheschans themselves. Importantly, Rheschans’ self-sufficient nature (in the sense of not needing ample amounts of outside trade) left them largely uninvolved in foreign affairs, eventually rendering them completely indifferent to anything outside their borders.

Circin was the land of snow and mountains, situated farthest north and falling into a small strip of desert along its southern border. The Circinians, despite having the fifth most polluted magic in Amral, undisputedly made the most practical use of it. The conditions many of them lived in were intolerable to ordinary humans, so, over the years, much of their land’s magic went into giving them some immunity to the cold. To supplement this, they became excellent with textiles, weaving intricate rugs for the bottom of their easily-portable tents (landslides were a constant threat) and fashioning amazing coats to balance the wearer’s temperature regardless of the weather. They held a serious grudge against the Lamaerans–a sentiment strongly returned–because of various land wars between the warmth-desiring former and the height-loving latter.

Loprena was hill country. Its people were famous for animal farming and sheep herding, as the nation was fully of grassy waves spreading out onto the horizon. They could usually be found living in small villages in warm cottages, drinking locally-made beer and wine, holding dances, and just generally enjoying a quiet country life. Most Loprenans had no desire to ever leave their little bubble, and there was almost no ambition to be found anywhere in the land. Far from stagnating them, however, the people’s patent humility allowed them to remain ever at peace, a place of rest for the world-weary traveller. And Loprenans loved travellers. Far from being cloistered and small-minded, they were more than willing to accept just about anyone into their fold for any length of time. That being said, they considered discussions of politics and economics to be in bad taste, and they would quickly change the subject whenever foreigners brought them news of the outside world. They were, in truth, consummate small-country folk, but they were as loving and kind as any you’d ever meet.

Maranthall was the meadow country, full of prairies and wildflowers. While there was some wild game to hunt, the land lacked the abundant natural resources its neighbors, leading some scholars to theorize that the richness of a land’s resources may have been related to the purity of its magic. That being said, Maranthall was far from the least important nation, although it was certainly the least appreciated. It was situated in the very center of Amral, rendering it the only completely landlocked nation, but this curse was also a blessing: it was ideally placed to benefit from trade. Maranthall effectively ran the Amralan trading network, extracting fees from internationally-bound goods in exchange for quicker, safer passage. Also, it stood as a neutral (yet still politically active) ground for mediating between hostile nations. Delegates from Ithwon and Ashtabar often met on the fields of Maranthall, as did those from Lamaera and Circin. Maranthall was the secret administrator of Amralan affairs: never thanked, rarely acknowledged, but vitally important to the continuance of world peace.

This has been a brief overview of Amral as it existed when Alkanion Ephenor, the hundredth king of Ithwon, was born. His name will be recognizable to any familiar with Amralan history, or to any of those following the book being written about his exploits and conquests: The Radiant City. Please reference that ongoing work for greater insight into how that one man–as noble as he was infamous–altered this history in indescribable ways.