From the perspective of Amral in Alkanion’s day, the Mornai were shadows from a time long past. They were elf-like creatures, beautiful and elegant with heightened senses and physical prowess, but, while their lifespans were quite a bit longer than a human’s, they were not actually immortal. It was possible to kill them, they had their share of diseases, and, even left perfectly healthy, they rarely survived past seven thousand years.

From the time the Mornai first ventured into Amral, thousands and thousands of years before the nations every developed, there were two distinct groups: the Karthai lived in the northern half of the country, while the Tarkai lived in the southern half. They got along in relative harmony–mainly by ignoring each other–and survived off of agriculture and fishing. At first, both groups refused to hunt, believing the taking of innocent life to be an abomination to Erfeirin, but as time passed they realized this was not the case, and practiced it in moderation.

In the beginning, the two groups looked very similar to each other (being of the same species); each bore light-colored skin and hair ranging from light blond to medium brown. Their eye colors, in contrast to humans, encompassed most of the spectrum, although brown was still the most common color.

However, as time passed and their respective societies developed, the differences between them became clear. The Karthai‘s skin and hair both grew somewhat lighter in response to their surroundings, reflecting the land’s magic that had so long been part of their lives. The Tarkai, meanwhile, tanned in the sun, their skin growing a deep caramel color.

Their cultures became more extreme, too. The Karthai, always solemn, became ice statues, locking away any emotions they felt deep inside, never showing more than a small smirk or pinch of the brow. They walked around with an air of regality, dressing themselves in thick, lush fabrics that flowed like silk and glistened like the sun on the snow. Relationships of any kind–familial, friendly, romantic–were discouraged, and, after a while, all but disappeared. There was little need, they decided, for romance in a society that could survive without a single child for millennia. Precious few Karthai ever fell in love or got married.

That was not to say they were cold-hearted. The Karthai loved each other deeply in their own detached way, and they cared immensely for the lands they tended. When winter cut them through to the bone, they would huddle together and sing beautiful songs about summer, their chorus echoing for miles around. When children were born, they were everyone’s children; even the coldest of men could not help but smile when a baby was thrust into their arms, laughing wildly. When springtime or harvest arrived, they set aside their dignity for a while to celebrate their good fortune. The emotions they didn’t allow themselves to feel thus manifested themselves in new ways.

The Tarkai, in contrast, took the exact opposite approach. Their lands maintained a relatively hotter atmosphere year-round. Always the more impulsive group, their emotions grew more and more volatile as time passed; whatever they felt–joy, rage, sadness, surprise–was written upon their face like a beacon. Or a warning sign. They harbored none of the qualms of their northern neighbors regarding relationships; although they still tried to limit the number of children they conceived, friendships and romances were common and–unless a couple chose to enter into the sacred institution of marriage–were viewed as entirely changeable things.

The Tarkai celebrated everything–the full moon, harvest, birthdays, anniversaries, sunrises, sunsets, rain, sunshine–but they were also hard workers, spending quite a bit of time slaving away in the sunshine. As such, their clothes, while still luxurious, were more practical than that of the Karthai. Hunting was far more prominent among them than among the Karthai, and they also spent more time gathering, despite the fact that agriculture provided most of their food.

Slowly, the situation between the two groups of Mornai deteriorated; they could no longer deny each other’s existence. The Karthai began to view the Tarkai as blood-soaked, violent people whose unpredictable emotions rendered them a threat to Karthai culture, since there was no knowing when they might attack. The Tarkai viewed the Karthai as prideful and snobbish, even more so because of their trademark reticence in showing emotion. They thought the Karthai were jealous of their better climate and would mount an invasion of it, one that would end with the subjugation and eventual extinction of Tarkai culture. Both sides were wrong.

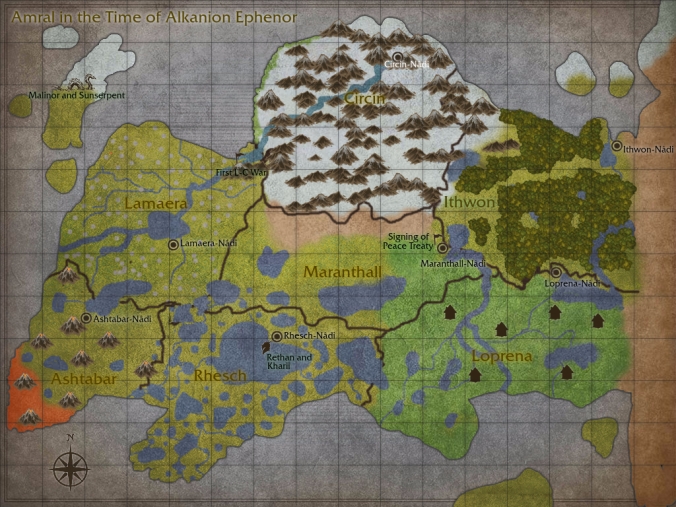

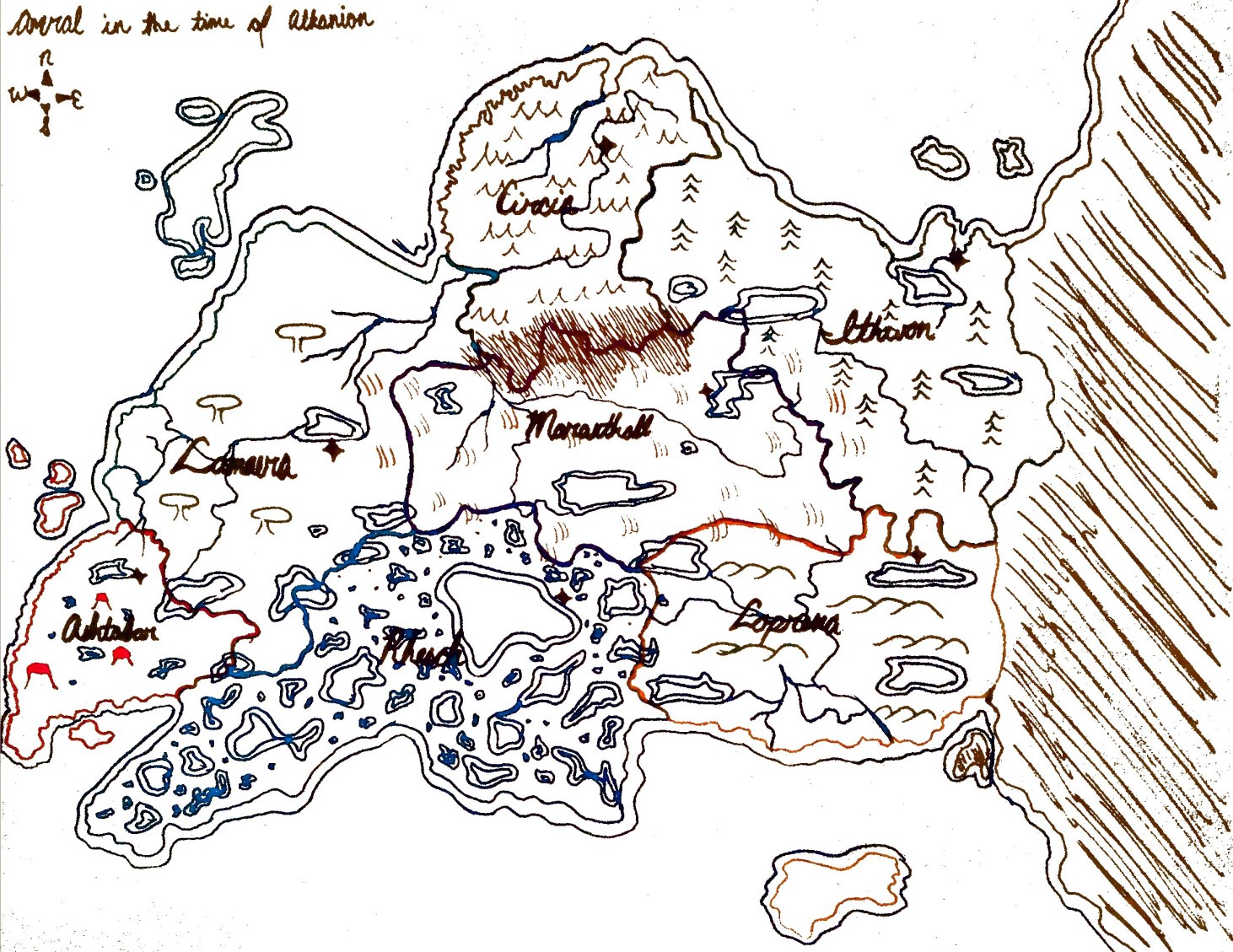

Things came to a head one day when a Karthai and a Tarkai met in the middle of what is now Maranthall, on the unofficial border between the two territories. Words were exchanged, weapons were drawn, and, in the absence of witnesses, no one knew who had struck first. All they knew was that it was the beginning of war.

The battles raged on for the better part of a millennium. Populations on both sides depleted to critically low levels, and childbirths began to occur with increasing regularity. The last straw was one ploy instituted out of utter desperation in which, to preserve the future of their species, they sent in some of the older children to fight instead of the last able-bodied men. None of them came home.

Six hundred years to the day since the fighting began, both sides agreed that a diplomatic meeting was necessary to avoid complete mutual destruction. They met on the fields of Maranthall, where so much killing had taken place, and waded through the many bodies the survivors had had to leave behind. In a pool of their brothers’ blood, they discussed their future.

In the end, it was decided that there was too much strife between the Mornai to share the same space. All agreed to take their chances sailing to foreign lands, where they could start a new life. The knowledge of how to cross the perilous eastern desert had long been lost, so, in keeping with the theme, the Karthai went north, the Tarkai south.

In the new lands they found, their respective cultures flourished, and the differences between them grew right along with them.

The Karthai, always pale, now seemed so light as to be made of ice and snow. Their hair was silver as the moon, their eyes as icy blue as the sky on a clear day, their skin so white that, in the sun, one could see the web of blue veins under their skin. Even their blood, thick with northern magic, took on a purplish tinge.

The Tarkai, likewise, moved towards their extreme. Their skin was a deep, rich walnut color, their hair as black and smooth as the night, and their eyes a brilliant gold, reflecting even the slightest bit of sunlight. Their blood ran redder than ever–and warmer, pulsing through their heart with an enchanted heat.

Centuries passed. Then millennia. The old generation died out, and the new generation began to forget the war stories. After an age of telling and retelling, the trials of the ancients faded into legend. The blood soaking the grounds of Amral cleared with every sprinkling of rain, and, soon enough, the Mornai on either side began to even question the land’s existence. By the time the humans arrived, they’d written it off entirely…